Jeremy Wells

Full-stack software developer sharing learnings with .NET, Angular, and anything else worth tinkering with

Setting up an N-Tier ASP.NET Core App

Photo by Elena Koycheva on Unsplash

Introduction

This is article #1 in a series of tutorials that walks through building and hosting an Angular and ASP.NET Core web application. The application will have extremely minimal functionality - a Walking Skeleton - but it can serve as a template for building out functionality in more useful projects.

In the previous article, I gave a more detailed overview of this series and walked through preparing a development environment for .NET Core. I also created and explained the default boilerplate code that comes from creating an ASP.NET Core WebApi application. For a little more background, I suggest reading through that article first before stepping through this tutorial.

Prerequisites

For this tutorial, I'll assume you'll aren't yet familiar with ASP.NET Core, but you have the .NET Core SDK and an IDE or text editor set up and ready to go, If not, the previous article will go through that step. If this is your first time building a server-side application, or if you're familiar with a comparable framework like Rails or Django, but haven't tried one from the .NET Core family, then hopefully this article will clearly introduce you to the process with this framework. I won't go into the syntax of the C# language (for that, I recommend Microsoft's introduction), but I'll explain the steps of building our application in detail.

N-Tier architecture

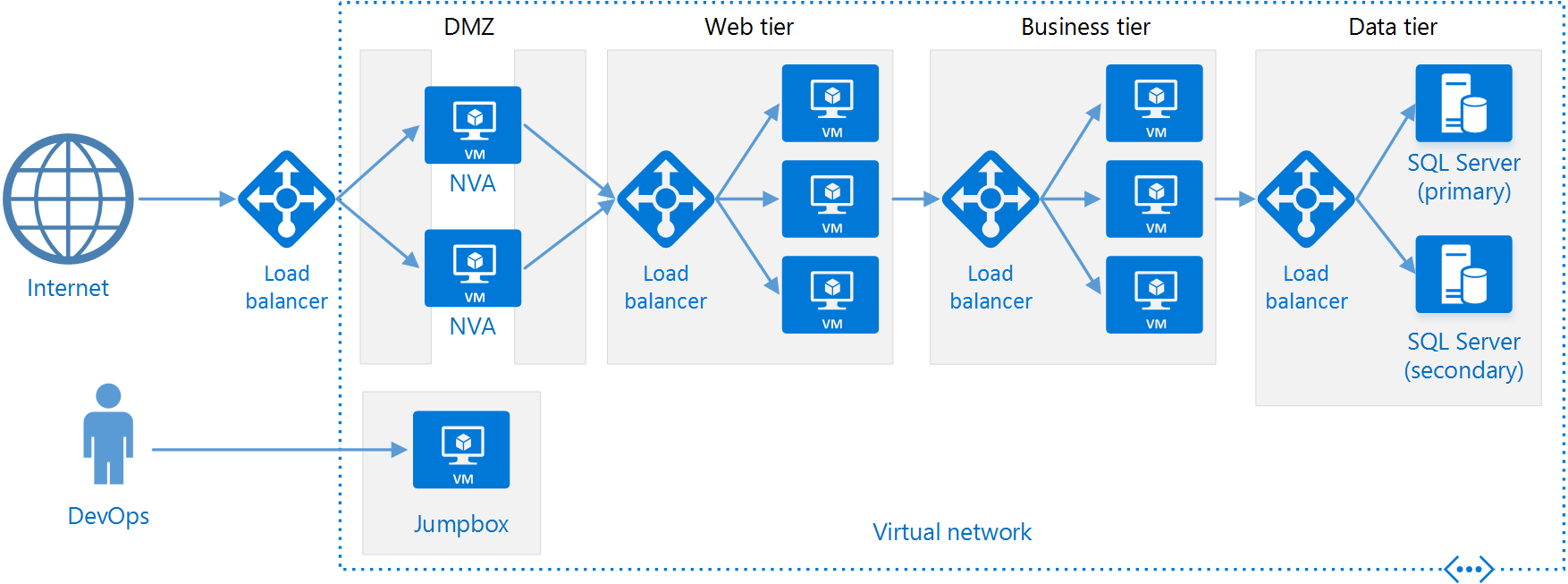

A common design pattern for web applications is called the N-Tier Pattern, where n is the number of layers of the application. Wikipedia describes one N-Tier scenario as a presentation tier, a logic tier, and a data tier:

Source: Wikipedia

An important feature of this pattern is that a lower layer is not aware of any higher layers and changes to a higher layer do not affect lower layers. This pattern can present itself as simply a separation between client-side code, a service layer that contains the business logic, and a data-access layer for interfacing with a database. And this Microsoft Azure article describes a much more scaled version of this pattern that separates the tiers into a number of physical processes:

Source: Microsoft

In our very simple application, the presentation layer will be an Angular client that we'll build in a subsequent article. Our controller will represent a web tier and in this tutorial, we'll build and secure a service as a business-logic tier that will call an external API.

The result will be an API endpoint that returns the next 5 temperatures in a forecast by location.

Here are the steps to get there:

- Sign up for and retrieve an API key to use the OpenWeatherMap service.

- Secure the API key so that it can be used in our application.

- Build a service that handles requests to the OpenWeatherMap API.

- Modify the controller to work with the service, then test it in Postman.

Going through these steps will demonstrate how ASP.NET Core uses dependency injection, protects sensitive values such as API keys and database connection strings, and how it handles exceptions.

The starting point for this code can be found at this repo. Using Git, you can clone the repo locally using:

$ git clone -b 0_GettingStarted --single-branch git@github.com:jsheridanwells/WeatherWalkingSkeleton.gitThen restore the project:

$ dotnet restoreGetting the OpenWeatherMap API key

Instead of returning random objects in the boilerplate code, we'll return values from a live API. The OpenWeatherMap API is an easy way to incorporate third-party data when testing out a project. You'll need to create an account, then get an API key to be able to make requests from their service.

- Go to https://OpenWeatherMap.org/api and click "Sign in". Create an account if you haven't before and log in.

- If you are at home.openweathermap.org, at the top of the page is a nav item called "API keys". Click that and you'll arrive here.

- Click the "Generate" button. Name the key and save it.

- The table will now list your API key. We'll copy this in the next step so that it's available in our application.

At this point, we can test out the OpenWeatherMap API to get an idea of the data structure it returns. Postman is a great tool for this. You can download it from here if you don't have it yet.

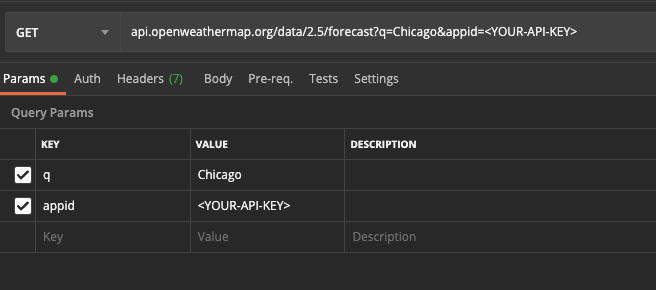

We'll test out the 5-day Weather Forecast endpoint. There are a variety of ways to query this resource: We'll query it by city name.

According to the documentation, the structure for the url is

api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast?q={ city name }&appid={ your api key }

We'll set that up in Postman by entering the url up to the resource name (forecast), then entering a city name and our api key in the query parameters table below. Also, you can add a units parameter with a value of either metric or imperial, otherwise the temperatures will be returned in Kelvin. Since I'm writing from the United States, I've opted for imperial.

If everything is set up correctly, your response will be an array of 40 temperature objects for whatever city was selected. We'll keep Postman open so that we can use the URL that was formed when we create a service in our web API to make this request.

Securing our API key

Although I'm having a hard time imagining what mischief could be made with my OpenWeatherMap API key, it's still best practice to store the actual value separately from the source code. In a real project, there will be all kinds of secret keys, passwords, and database connections strings - and these values would be different from environment to environment - so here we'll save the API key in our file system, then bring it into our application configuration. The User Secrets API that comes with the dotnet SDK is an ideal tool for this.

To accomplish this, we'll:

- Create a class to help inject our key in the places where we need it.

- Save our key to the file system using the

dotnetcli. - Bring our key into the configuration schema in our project's

Startup.csclass.

First, we'll create a class called OpenWeatherMap and give it one property: ApiKey:

$ mkdir Config

$ touch Config/OpenWeather.cs(Note: if you're using Visual Studio, you can create this file using the Solution Explorer)

Add these contents to OpenWeather.cs:

namespace WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Config

{

public class OpenWeather

{

public string ApiKey { get; set; }

}

}When the dotnet CLI saves secrets for a project, it's in a directory structured as follows:

$ ~/.microsoft/usersecrets/<USER-SECRETS-ID>/secrets.json

The USER-SECRETS-ID is saved in the .csproj file at the root of the project. Any string will work as a user secrets ID, but for this project we'll use a GUID: 65988f0a-26ed-44ef-8749-f86a2f5c18a9 (you can also generate your own GUID if you prefer).

Open WeatherWalkingSkeleton.csproj and add the UserSecretID:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Web">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp3.1</TargetFramework>

<UserSecretsId>65988f0a-26ed-44ef-8749-f86a2f5c18a9</UserSecretsId>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>Next, run the following command, replacing YOUR-API-KEY with the API key you generated when signing up for the OpenWeatherMap service:

$ dotnet user-secrets set "OpenWeather:ApiKey" "YOUR-API-KEY"If you're successful, you should see output like this:

Successfully saved OpenWeather:ApiKey = YOUR-API-KEY to the secret store.

Now that the key value is stored in our usersecrets/ directory, we need to bring it into the application. This is done in the Startup class by calling a method from the Configuration object, then adding it to the application's service collection:

// Startup.cs

using WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Config;

// [...]

public class Startup

{

// [...]

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

// Add OpenWeatherMap API key

var openWeatherConfig = Configuration.GetSection("OpenWeather");

services.Configure<OpenWeather>(openWeatherConfig);

// [...]

}Now the API key is available in the application when we use the OpenWeatherMap API. We'll be able to confirm that later when we build a service to call the API.

Classes for mapping the OpenWeatherMap API response

Our next step is to create a service to sit between the WeatherForecastController and the OpenWeatherMap API. Ideally, a controller's only responsibilities are to route requests to the right services and to return either success or error responses. All the business logic should be handled at the lower levels.

Before implementing the actual service though, we'll need to create a class to deserialize the response we get from the OpenWeatherMap API. We'll also create a class for our own API response that will organize the data the way we would like to present it.

First, delete the default ./WeatherForecast.cs class that was created when the project was bootstrapped.

We'll create a Models/ directory, with two classes: a new and improved WeatherForecast which will be the object that gets returned from the WeatherForecastController, and an OpenWeatherResponse which we'll use to deserialize the JSON data returned from OpenWeatherMap.

$ mkdir Models

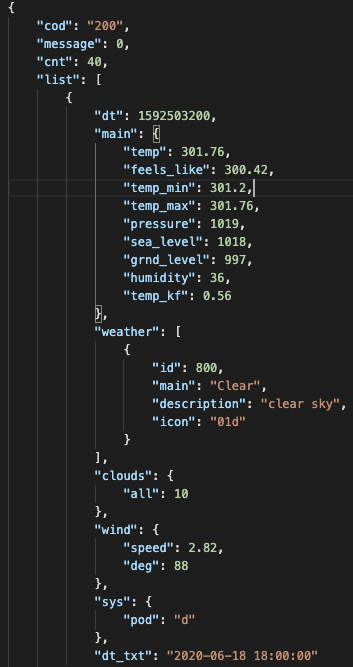

$ touch Models/{WeatherForecast.cs,OpenWeatherResponse.cs}After inspecting the response from OpenWeatherMap in Postman,...

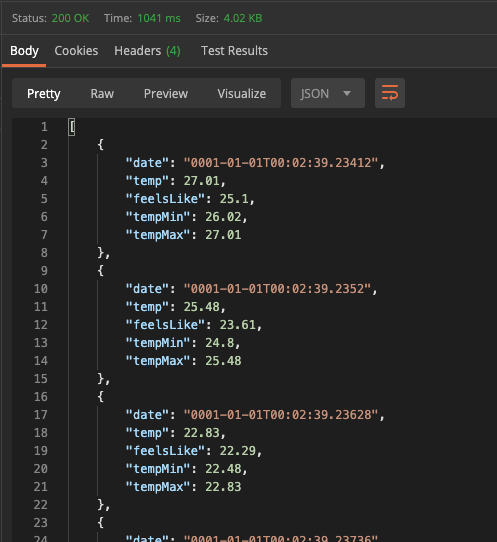

...we see an array called list. I've decided that I'd like our API to return the date and time, temperature, the "feels like" temperature, as well as the min and max temperatures for each item in that array. We'll add those properties to the WeatherForecast model.

// WeatherForecast.cs

using System;

namespace WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Models

{

public class WeatherForecast

{

public DateTime Date { get; set; }

public decimal Temp { get; set; }

public decimal FeelsLike { get; set; }

public decimal TempMin { get; set; }

public decimal TempMax { get; set; }

}

}Feel free to experiment and extract different kinds of values from this response as you follow along.

This class is pretty straightforward, but extracting these values from the OpenWeatherMap response, a rather complex JSON object, will take more work. The response is organized as follows:

- The root object contains an array property called

list. - Each item in

listcontains a Unix timestamp calleddtand an object calledmain. mainthen holds the different temperatures that we want.

To deserialize this response into a C# object, we'll create three classes, and leverage a library called System.Text.Json which is included in ASP.NET Core as of version 3x.

Add the following to OpenWeatherResponse.cs:

// OpenWeatherResponse.cs

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Text.Json.Serialization;

namespace WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Models

{

public class OpenWeatherResponse

{

[JsonPropertyName("list")]

public List<Forecast> Forecasts { get; set; }

}

// [... continue to add here]

}We'll name the root object OpenWeatherResponse. The System.Text.Json library provides a data annotation called JsonPropertyName which allows us to indicate the json property that we're extracting these values from. This way we can take an array originally called list and name it something more meaningful in this context: Forecasts.

We'll create a Forecast class that will hold the dt and main properties from the API response:

// OpenWeatherResponse.cs

// [...]

public class Forecast

{

[JsonPropertyName("dt")]

public int Dt { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("main")]

public Temps Temps { get; set; }

}

// [...]By taking the values from main and renaming them Temps, our own code will be easier to understand.

Below the Forecast class, we'll add the final class called Temps to indicate which temperature values to include. As before, we can use JsonPropertyName to name our properties with the conventional C#-style casing.

// OpenWeatherResponse.cs

// [...]

public class Temps

{

[JsonPropertyName("temp")]

public decimal Temp { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("feels_like")]

public decimal FeelsLike { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("temp_min")]

public decimal TempMin { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("temp_max")]

public decimal TempMax { get; set; }

}

// [...]Now that a strategy for handling the API data is in place, the next step is to call the API with a service.

Setting up and injecting an ASP.NET Core service

As mentioned earlier, ASP.NET Core uses dependency injection as a primary design consideration, and we'll see how this works here as we implement a service that calls the OpenWeatherMap API and returns the data as a WeatherForecast object. Our service will be called OpenWeatherService with a method called GetFiveDayForecast. The method will take a location and a unit of measurement to use when calling the API. The service will be represented in other classes as an interface called IOpenWeatherService.

We'll build it in such a way that we can verify that the service is wired up correctly in the application first before getting into actual functionality: We'll create the service class, create the interface, register the types in Startup, then inject them into the WeatherForecastController. After these steps, we'll implement the actual GetFiveDayForecast method.

Create a new file to hold the service and the interface:

$ mkdir Services

$ touch Services/OpenWeatherService.csNormally, we would have the interface and the class in separate files, but since this class will only have one method right now, we'll keep them together. Add the following to create the IOpenWeatherService interface:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Models;

namespace WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Services

{

public enum Unit

{

Metric,

Imperial,

Kelvin

}

public interface IOpenWeatherService

{

List<WeatherForecast> GetFiveDayForecast(string location, Unit unit = Unit.Metric);

}

// [...]

}Our interface defines a method that accepts a location and a unit of measurement, and we've restricted it to the three acceptable options using an enum. The method will return a list of objects of the WeatherForecast type that we defined earlier.

Below the interface we'll add a service class to implement the method:

public class OpenWeatherService : IOpenWeatherService

public List<WeatherForecast> GetFiveDayForecast(string location, Unit unit = Unit.Metric)

{

return new NotImplementedException();

}So far, the only thing the method does is raise an exception to say it's not ready yet. We'll leave it this way for now so that we can register it in the Startup class and inject it into the controller. Then we can do a quick test with the controller to make sure the method is getting called. After that, we'll build out the method.

Open Startup.cs again and find the ConfigureServices method. Below the line where we brought in the API key, add the following line:

public class Startup

{

// [...]

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

// [...]

services.AddScoped<IOpenWeatherService, OpenWeatherService>();

// [...]

}

}services.AddScoped is the method telling the application to instantiate an OpenWeatherService object whenever another class depends on the IOpenWeatherService interface. ASP.NET Core provides three methods for registering dependencies: AddSingleton which initializes an object once during the application lifecycle, AddScoped which keeps the same object available during a single request before disposing it, and AddTransient which provides a new instance every time it is injected. The Microsoft docs explain service lifetimes in more detail.

Next, we'll modify the WeatherForecastController to return data from the OpenWeatherService instead of random values.

First, we will inject IOpenWeatherService in the class constructor and make it available as a private property called _weatherService.

using WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Services;

namespace WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Controllers

{

public class WeatherForecastController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly IOpenWeatherService _weatherService;

public WeatherForecastController(ILogger<WeatherForecastController> logger, IOpenWeatherService weatherService)

{

_logger = logger;

_weatherService = weatherService;

}

// [...]

}

}Next, we'll change the Get method to use the data returned from the service.

[HttpGet]

public IActionResult Get()

{

var forecast = _weatherService.GetFiveDayForecast("Chicago");

return Ok(forecast);

}

}Anything else in the controller can be deleted.

Instead of producing values directly in the controller, we're returning the result of data produced elsewhere, so our return type will be IActionResult. We're receiving an object we'll call forecast from the OpenWeatherService, and we'll pass it on in the body of a "Success" response: Ok(). Also, for now, I've hard-coded "Chicago" as the argument for GetFiveDayForecast to that everything will compile. Later, we'll modify Get again to accept query parameters.

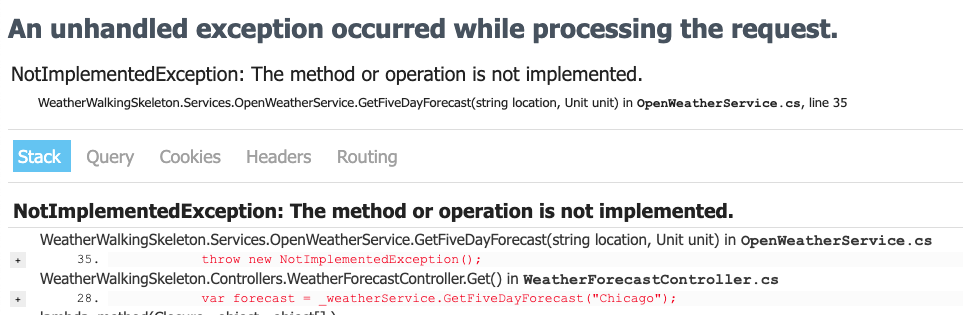

Let's do a quick test to make sure that OpenWeatherService.GetFiveDayForecast() is being called within the application. Run the application ($ dotnet run) and call the WeatherForecastController from Postman or a browser (https://localhost:5001/WeatherForecast). The response we expect looks like this:

Since the stack trace is throwing a NotImplementedException called from the OpenWeatherService in our WeatherForecastController, everything is working as expected. Now, we'll make our five-day forecast method actually work.

Implementing our HTTP service

Open OpenWeatherService.cs back up. The plan for our GetFiveDayForecast method is for it to do what we were doing before in Postman: make a GET request to the OpenWeatherMap API and map the values we want as a list of WeatherForecast objects.

The first thing to do is to build a URL so that it looks like the URL that was successful for us when testing the API in Postman, e.g.:

api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast?q=Chicago&appid=YOUR-API-KEY8&units=imperial

First, we need to extract the API key from the configuration of our application. At the top of the class we'll create a constructor that injects an instance of IOptions:

using Microsoft.Extensions.Options;

using WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Config;

// [...]

public class OpenWeatherService : IOpenWeatherService

{

private OpenWeather _openWeatherConfig;

public OpenWeatherService(IOptions<OpenWeather> opts)

{

_openWeatherConfig = opts.Value;

}

// [...]

}Using the OpenWeather type, we can deserialize the value of our API key from the local environment without having to write it anywhere in the code. We'll store it as a private property called _openWeatherConfig. With the API key, along with the location and unit of measurement coming in as method arguments, we have the values needed to build the URL. We'll do that on the first line of the GetFiveDayForecast method:

public List<WeatherForecast> GetFiveDayForecast(string location, Unit unit = Unit.Metric)

{

string url = $"https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast?q={ location }&appid={ _openWeatherConfig.ApiKey }&units={ unit }";

// [...]

}If you are handy with the debugger in the IDE that you're using, you should set a breakpoint here and inspect the value of _openWeatherConfig.ApiKey.

Next we'll create a list of forecasts that the method will return:

using WeatherWalkingSkeleton.Models;

// [...]

public List<WeatherForecast> GetFiveDayForecast(string location, Unit unit = Unit.Metric)

{

string url = $"https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast?q={ location }&appid={ _openWeatherConfig.ApiKey }&units={ unit }";

var forecasts = new List<WeatherForecast>();

return forecasts;

}In the middle is where we add the logic to:

- Make a GET request to the OpenWeatherMap API,

- Deserialize the response,

- And use the response to build the list of

WeatherForecastobject we're returning.

That implementation can be described as follows:

// 0. Use the .NET HttpClient library

using (HttpClient client = new HttpClient())

{

// 1. Make the request

var response = client.GetAsync(url).Result;

var json = response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result;

// 2. Deserialize the response.

var openWeatherResponse = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<OpenWeatherResponse>(json);

// 3. Build the list of forecasts

foreach (var forecast in openWeatherResponse.Forecasts)

{

forecasts.Add(new WeatherForecast

{

Date = new DateTime(forecast.Dt),

Temp = forecast.Temps.Temp,

FeelsLike = forecast.Temps.FeelsLike,

TempMin = forecast.Temps.TempMin,

TempMax = forecast.Temps.TempMax,

});

}

}The entire method should now look like this:

public List<WeatherForecast> GetFiveDayForecast(string location, Unit unit = Unit.Metric)

{

string url = $"https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast?q={ location }&appid={ _openWeatherConfig.ApiKey }&units={ unit }";

var forecasts = new List<WeatherForecast>();

using (HttpClient client = new HttpClient())

{

var response = client.GetAsync(url).Result;

var json = response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result;

var openWeatherResponse = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<OpenWeatherResponse>(json);

foreach (var forecast in openWeatherResponse.Forecasts)

{

forecasts.Add(new WeatherForecast

{

Date = new DateTime(forecast.Dt),

Temp = forecast.Temps.Temp,

FeelsLike = forecast.Temps.FeelsLike,

TempMin = forecast.Temps.TempMin,

TempMax = forecast.Temps.TempMax,

});

}

}

return forecasts;

}Start the application again, make the same API request to /WeatherForecast and we should now see actual data.

The final bit of functionality we'll need is to update the controller so that we can also send location and unit of measurement parameters with our requests. Back in WeatherForecast.cs, we'll add two arguments to the Get method and use those when we call GetFiveDayForecast:

public IActionResult Get(string location, Unit unit = Unit.Imperial)

{

var forecast = _weatherService.GetFiveDayForecast(location, unit);

return Ok(forecast);

}The ASP.NET Core ControllerBase class has several ways to extract parameters and data from HTTP requests. Here, if we simply add arguments to a controller method, and add the matching names in the URL...

https://localhost:5001/WeatherForecast?location=london&unit=kelvin

...the controller will bring them in as parameters.

Run the application again, make a POSTMAN request at the above url. If everything is great, you should see a response like this:

Summary

Now that we've got an API of our own returning real data, now is a good stopping point before building in a little more infrastructure in this project. We'll do that in future tutorials.

Using the above steps, we were able to conceal a secret API key using .NET Core's user secrets. We built out a service class to pull data from an external resource and modified a controller class so that it is limited to simply relaying requests and responses. We also saw how the Startup class in an ASP.NET Core application sets up dependency injection and configures services using values from the host environment. With this basic functionality in place, we'll be able to explore some of the other necessary components to deploy a working walking skeleton and have a solid reference for putting together our real projects.

To reference the code that was created in this tutorial, see the 1_aspnetcore_webapi_setup branch in its Github repo.